- Home

- Courtney Milan

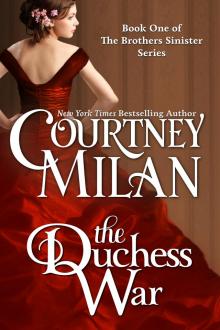

The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister) Page 25

The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister) Read online

Page 25

He grinned at that memory—of his mother writing profanity about his father—while Minnie looked on aghast.

“Of course I asked her, ‘What is a bugger?’ Thus was my childish attempt at fraud revealed. I had just proven that I could read. She didn’t say a word. She simply stood up and left the room. She and my father had the most frightful row after that. I believe that she actually threw things at him that time around. And I didn’t see her again for almost eighteen months.”

Minnie didn’t know what to say. He stood there, smiling, as if he’d just related a funny little story—like the anecdote Minnie might have told about the time she got lost when she was seven and put her hand in another man’s pocket, thinking he was her father.

“God,” he said, “I can’t believe what an unworthy little cad I was.”

How could he smile about his father conscripting him at the age of six, using him as a weapon against his own mother? How could he laugh about his mother walking away from him? How could he pretend there was anything amusing about the fact that his father took a newborn babe away from its mother in order to get more money out of her?

“You know, Robert,” she said, choking on the words, “there is really nothing funny about that story. Nothing.”

Slowly, the smile on his face faded. “You didn’t think so? But…” He frowned and rubbed his chin. “Not the first part, I understand that. And…and I suppose it’s not precisely a story that ends happily. I hadn’t thought of that, but I’m so used to the ending that I think nothing of it. But the middle bits—surely those were funny. Weren’t they?”

“When you changed the primer to M-is-for-Mama, did you mean it?”

For one second, there wasn’t the slightest hint of amusement in his eyes. He looked so old, the tiny lines at the corner of his mouth gathering as his lips pinched together. And yet he also looked young—impossibly young, as if his six-year-old self were still looking out from behind his eyes, watching his mother walk away.

“Maybe.” He looked away from her, and then looked back. That urbane amusement was back on his face now, but it looked lopsided on him—as if he were trying to wear a hat that didn’t quite fit.

“That’s why it’s not funny.”

“There are funny elements to it,” he protested. “Adding five and six and getting thirteen?”

His hand had cinched itself more tightly about her elbow. He didn’t throw the next piece of bread to the ducks so much as hurl it so hard that one of them quacked in surprise and darted away before realizing that it was fleeing food. And perhaps that was when she realized how much it meant to him. It had to be a funny story to him. This little tale about telling lies at his father’s behest and wanting, so desperately, for his mother to stay—this was a story about the breaking of his child’s heart.

This was the man who had understood that marriage to the expected noble’s daughter would end in regret and recrimination if it came out that he intended to abolish the peerage. He knew in his bones what it meant to have a wife walk away from him, and he’d rejected the possibility—rejected it, even though it would mean gossip and scandal, even though it would certainly mean that the highest sticklers in society would never accept his family.

He didn’t look at her. “That bit about skipping portions of the alphabet? Surely that’s at least a little amusing?”

This was a man who wanted his wife to love him, but who would not even allow himself to hope for it. And that was when Minnie realized that she had something he’d never had. She’d been loved. Her father had adored her up until the moment when his pending conviction had broken his spirit. She had happy memories, years of them, with him. After he’d disappeared, her great-aunts had swept in. She might not agree with everything they’d told her, but they’d loved her. They’d treated her as if she mattered. She took love for granted.

Lucky her.

He had to laugh at what had happened. If he didn’t laugh, he would cry. She couldn’t have understood it until just that moment—because at that moment, she knew that she had to laugh, too, or burst into tears on his behalf. He looked at her with such urgency that she could not bear to force the issue.

“Yes,” she said quietly, entwining her fingers with his. “I do see that, now. It is funny.”

THOSE FIRST DAYS IN PARIS seemed like jewels to Robert. As if he’d lived all his life behind clouds and the sun had come out in blinding force.

They woke. They walked. They visited museums and places of interest; they found their way back to their rooms in the afternoon and made love. Boxes at the opera went unused in favor of more time in bed.

“You said you thought of me on my knees,” she said one afternoon. “How on earth would that work?”

So he’d explained. And then she’d insisted on trying it—and after a little instruction, trying had turned into his cock hard in her mouth, his hands on her shoulders. He’ gasped as she took his length until he spilled. After that, it had only seemed fair to return the favor. It had taken him a little longer to grasp the gist of it, but it was worth the effort.

If you’re good in bed, I might fall in love with you.

He was determined to become good, and he had years of fantasies to explore.

Sometimes, the things they imagined proved anatomically impossible, and they ended up collapsed in a laughing heap on the floor. Sometimes—like the time he bent her over the desk—it was very, very good.

On their fourth night in Paris, he put rubies around her neck—just rubies, after he’d taken everything else off—and had his way with her.

Afterward, she fingered the gems around her neck. “Are these supposed to be a bribe?” she asked. “You should realize by now that you don’t have to offer me anything to get me in your bed.”

“I would realize that,” he said cheerfully, “but luckily for you, lust makes me stupid. You get rubies.”

She had only smiled.

But she’d been right. They had been a bribe. Not for her favors; he didn’t like the idea of paying for sex as a married man any more than he had as a bachelor. But by this point, he wanted her to love him. He wanted it with a deep yearning that he couldn’t have explained. He almost told her himself that night, that he loved her. But they had nearly a week left. There was time for love to come. No need to rush at all.

He fell asleep with his arm around her and woke the next morning in the same position. The rubies at her throat winked at him in the early light, a blood-red portent of things to come.

He stared at them and shook his head to clear it of such a strange, unsettling thought.

And that’s when someone pounded on the door.

MINNIE WOKE TO A COLD DRAFT and the memory of a ruckus. She opened her eyes; their bedchamber was empty. She blinked and looked around. It was only then that she heard the murmur of voices in the main salon. She got up, found a robe, and made her way to the door between the rooms.

There was a garçon standing there. He handed Robert, who was also encased in a dressing gown, a plain brown envelope. Robert slipped him a coin. “Wait outside in case there’s a need for an immediate reply.”

He shut the door.

“A telegram?” Minnie asked. “I hope it’s not bad news.” The rubies he’d put on her last night seemed heavy on her throat, out of place while she was garbed in nothing but an embroidered outer covering.

Robert slid his index finger under the flap to break the seal. “I’m going to guess it’s from Carter, my business manager. It can wait until after—” He spoke carelessly, flipped open the envelope, and glanced at the paper inside.

Minnie watched all the color wash from his face. He stared at the message, his lips moving softly. Finally he looked up.

“It’s from Sebastian.”

“Mr. Malheur? Your cousin, the scientist?”

His breath hissed in, snake-like. “That very man.”

“Robert, what is it?”

He was still staring at the page. His face seemed hewn from marble—hard and whit

e. “Tell Rogers to pack my things.” He spoke in cold, clipped tones. “He can have them on the next train.” He pulled a watch from his pocket, frowned at it, and then opened the door to the waiting garçon. “Send a reply: ‘I’ll be there immediately.’” He tossed another coin to the man, who disappeared.

Robert still hadn’t met Minnie’s eyes, but he turned around. “I must be on the nine-thirty express. That gives me almost an hour. I haven’t time to—”

“What’s wrong?”

She had to follow after him into the dressing room, trotting to keep up with his long strides.

The snarl on his lips softened momentarily as he looked down at her. “You stay,” he said more gently. “You’ve shopping to do, and there’s no need—”

She put her hand on his chest. “No need but the fact that I gave you my vows just days ago. Through better or worse, Robert. Do you think you’ll be running off on me already, leaving me here to guess what has happened? If you’re leaving, I’m coming.”

She had thought he might argue, but he simply shook his head and rang for his valet.

“What is it?” she asked again.

“It turns out they’ve charged a suspect with criminal sedition for distribution of my handbills,” Robert said. “Found—ha. Arrested. Indicted.”

“What? They’ve charged you in your absence?”

“No. Not me.” His lips curled even more. “The man they have is innocent, but that won’t stop them from pursuing the matter. Perhaps they think to embarrass me, without thinking that they’re destroying the life of a man who is, and always has been, my superior.”

“Who? Who is it?”

His face contorted, and his hands gripped hers. “Oliver Marshall,” he said. “My brother.”

Chapter Twenty-three

ON THE EXPRESS TRAIN FROM PARIS TO BOULOUGNE, Robert booked an entire first-class compartment. Not for luxury; he would hardly have noticed at this point. It was simple self-preservation. If he had to make polite conversation about his journey, he would never survive. Instead, he stared at the passing countryside as the sun climbed in the sky. The hours passed.

He didn’t sit in any of the comfortable seats, didn’t partake of any of the charming fruit-and-cream-laden pastries that Minnie must have ordered for him. He tried a biscuit at her urging, but it tasted like ash in his mouth, and he laid it aside after one bite. He stood near the front of the compartment, one hand on the wall, the other holding a cigarillo out the open window.

He’d long since realized that he used cigarillos as an excuse to avoid company. Now, the trickle of smoke that escaped into the compartment made another barrier, a hazy wall built between him and his wife. He took a drag on it anyway, and the smoke was acrid and harsh in his lungs, a more fitting punishment for what he’d allowed than his own guilt.

He’d known that Stevens wanted a culprit. He’d known, and in the haste—and lust—of his wedding, he’d put the matter off for his return. He thought he had time enough to deal with it.

The miles clacked past, marked only by his watch and the passing villages. Long hours slipped by, punctuated only by the shriek of the brakes and the whistle of the train for the few stops that the express made. First Beauvais, then Amiens, was left behind. It was only when the train skirted the silver-barked beeches of the Forest of Crécy that his wife braved the forbidding looks he gave her and crossed to him.

“You know,” she said, coming to stand by him near the farthest wall, “pushing won’t make it go faster.”

“No?” He tapped the end of his cigarillo out the window and watched embers fly away, pulsing briefly in the wind. “Doesn’t slow it down, either. Not that I can see.”

She looked away. Her fingers tapped against the window; her jaw squared.

A third punishment, that slight withdrawal, one that stung more than the smoke he’d inhaled.

But this way, you’re punishing her, too. His fist clenched and he shook his head.

She didn’t say anything. The train went around a curve; she put one hand against the wall to steady herself. The protest of the metal couplings, bending in place, surrounded them. The sound of the train, clack-clacking along at something just above thirty miles an hour, swallowed up any other response she might have given.

Not even one week married, and he was already fouling everything up. He’d wanted…so much. Not just a wife in name, but a family in truth. Someone who chose him.

Stupid bloody dream, that. At this particular moment, he wouldn’t have chosen himself, either. He gave the cigarillo another flick and watched orange sparks fly.

And that was when he felt her arm close around him from behind. She didn’t say anything at all, just pressed against him, holding him tight. She squeezed until it was clear that she wasn’t letting go, no matter how foul his mood. His breath rasped in his lungs, and this time not from the smoke.

“Oh, Minnie,” he heard himself say. “What am I going to do?”

“Everything you can. When is the trial?”

He shook his head. “I don’t know.”

“You’re a duke. There must be something you can do.” She paused. “Legal matters… I know almost nothing about them. But cannot trials be quashed?”

“This one, it’s intended to embarrass me,” Robert said. “Retaliation, I think.”

His face grew grim.

“There’s been something odd afoot in Leicester. I started looking into it because I discovered what my father had done with Graydon Boots. Those charges of criminal sedition always arose just when matters between workers and masters had come to a head. They’re grudges, not a proper application of the law.”

“All the easier to have it quashed, then,” Minnie said.

“Not that simple.” Robert tapped the cigarillo against the window frame once again. “Sebastian said they’ve already had a few reporters come in from London to cover the matter. It’s being reported that a man in my household committed a crime. Stevens no doubt thinks he has an easy conviction, that with me out of the country, I won’t be unable to respond. He thinks the damage will be done by the time I come back. I’ll be embarrassed, and Oliver—a guest of my house and a known associate—will be branded a criminal.”

“But that won’t happen,” Minnie said.

Robert was silent a little longer. “I could bring enough pressure to bear that the case would be dropped.”

Her arms tightened around him.

“But I can’t stop the talk that would result if I quashed the inquiry. My brother…he’s worked hard, so damned hard, to build up a store of respect for himself. He’s beginning to have a reputation as an intelligent, fair-minded man. If I quashed the inquiry—even if we won, eventually, on the grounds that the papers weren’t even seditious—the idea that he had written such radical sentiments under an assumed name would destroy everything he’s worked for. So, yes, I could stop the legal trial. But my brother doesn’t just need a favorable verdict. He needs to be publicly exonerated of the charge.”

“And you’ll see it done.”

She said it so confidently, so sweetly, that for a moment he almost believed her.

“I’ll do anything.” His voice broke. “My brother told me once that family was a matter of choice. If I were to turn my back on him now, what kind of brother would I be to him?” He let the cigarillo go; it swirled in the eddies alongside the train and disappeared around the bend before he saw it land. The forest passed by, receding in the distance. Now there was only rolling pastureland.

He counted three fences before he spoke again. “My father raped his mother.”

She sucked in her breath.

“That’s the claim I have on him—that an unwilling woman was once forced to my father’s will. That my family was so powerful that justice was subverted.”

“It wasn’t you.”

“It was the Duke of Clermont. I bear his name, his face.” His hands tightened into fists. “His responsibility. I suppose in some ways it was the height of

selfishness for me to even claim him as a brother. But I can’t let go. If family is a matter of choice, I’ll choose him. And I will, over and over, until—”

The thought was a crushing weight against his chest. He almost staggered with it. He did stagger, when the train shifted direction once more. But Minnie leaned into his shoulder, steadying him, and then guided him to sit on one of the cushioned benches.

“You’ll choose him until what?” she asked.

“Until the stars fall from the sky,” he said. “Because he chose me first.”

It was such a damning thing to admit, that vulnerability. He felt like a turtle, stripped of its shell, being readied for soup.

But she didn’t lift a brow at that. Instead, she stood before him, her skirts spilling around his knees. Her fingers traced his eyebrows, pressing against his temples before running back along the furrows of his forehead. It felt…lovely. As if she could coax the tense guilt from his features.

“My great-aunts used to do this for each other,” she said. “When things did not go well.”

He brushed her hands away. “I don’t need comforting.”

He didn’t deserve it.

But before he could stand up and turn away, she grabbed hold of his hands. Her grip wasn’t firm, but it was sure.

“If family is a matter of choice,” she said softly, “I’ve chosen you.”

He let out a long breath.

“And I will,” she said, “again and again.”

He lifted his head. Her eyes were wide and gray and guileless, and she was saying words that he’d longed to hear for years. On a breath, he stood, reaching for her. His hands closed on her hips; a scant few moments later, his mouth captured hers. There was no thought, no calculation in that kiss. She was simply achingly present.

“Minnie,” he murmured against the heat of her lips, and then again, “Minnie.”

Tonight would be the fifth night of their marriage. He’d had her while she laughed. He’d taken her while she moaned for him. He’d never taken her feeling as he did now—dark and uncertain.

Her Every Wish

Her Every Wish Midnight Scandals

Midnight Scandals After the Wedding

After the Wedding The Heiress Effect

The Heiress Effect Unraveled

Unraveled The Suffragette Scandal

The Suffragette Scandal The Year of the Crocodile

The Year of the Crocodile The Duchess War

The Duchess War What Happened at Midnight

What Happened at Midnight The Countess Conspiracy

The Countess Conspiracy Proof by Seduction

Proof by Seduction Unlocked

Unlocked Trial by Desire

Trial by Desire The Governess Affair

The Governess Affair Unveiled

Unveiled The Lady Always Wins

The Lady Always Wins Trade Me

Trade Me Unclaimed

Unclaimed This Wicked Gift

This Wicked Gift The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister)

The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister) Hamilton's Battalion: A Trio of Romances

Hamilton's Battalion: A Trio of Romances The Turner Series

The Turner Series The Suffragette Scandal (The Brothers Sinister)

The Suffragette Scandal (The Brothers Sinister) Seductive Starts

Seductive Starts The Pursuit Of…

The Pursuit Of… Hamilton's Battalion

Hamilton's Battalion The Carhart Series

The Carhart Series Seven Wicked Nights

Seven Wicked Nights This Wicked Gift (A Carhart Series Novella)

This Wicked Gift (A Carhart Series Novella)