- Home

- Courtney Milan

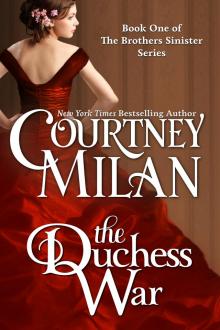

The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister) Page 30

The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister) Read online

Page 30

She turned back to his room. A newspaper lay on a chest of drawers. She unfolded it curiously and discovered that it had been printed this afternoon. It couldn’t have been more than a half hour old.

Duke of Clermont Authors Handbills, the headline proclaimed. In smaller type underneath, the subtitle read: Duchess Is Former Chess Champion.

She read that again, shaking her head at how bland it felt. “Well,” she finally murmured. “I suppose ‘Duchess is former fraud who dressed as boy and deceived hundreds’ wouldn’t fit. Three cheers for restricted paper size.”

The article itself was surprisingly evenhanded. The worst accusations she’d weathered in the past—monster, cheat, unnatural devil’s spawn—were absent. Her past was summarized in a short, factual paragraph. It was shocking, no doubt, but time had blunted the power and charisma of her father’s words.

Mr. Lane claimed the entire scheme was his daughter’s idea, but no evidence was ever found to support the assertion that a twelve-year-old child had been involved in the fraudulent endeavor.

She felt as if she’d opened a door on what she believed was a towering monster, only to find it five inches tall. There were things one might say about the child of a criminal. One didn’t say those things about a duke’s wife.

The account of today’s trial seemed equally strange.

Reading about her own collapse was a decidedly odd experience. It felt as if she were observing her emotions from a distance. She could hear the gasps of those around her in the courtroom, but now she understood them as surprise, not condemnation. She could see herself go pale, without her own skin going clammy, her breath cycling dangerously swiftly.

It allowed her to see what happened afterward, too. She’d fallen into a dead faint. A man near her had spat at her—and when he had, the dowager duchess had smacked him over the head with her umbrella. She’d glared at everyone else who threatened to close in, keeping them at bay.

Robert had leaped over three benches—surely that had to be an exaggeration—to reach her.

When the duke brought his wife out of the courtroom, he deigned to answer a few questions. He affirmed that he was aware of his wife’s identity on their marriage—a claim that seems unassailable in light of the marriage registry, which names his wife as Minerva Lane. His Grace explained his choice of bride as follows: “Why would I take a conventional wife, when I could have an extraordinary one?”

Minnie set the paper down and shut her eyes. Her eyes stung with prickling tears. She could hear him in that quote—could imagine the roll of his eyes, the look of annoyance he’d cast at them. Her body had the memory of being held, even if her mind did not.

She wasn’t sure what any of it meant, but she was sure of one thing.

He was coming back.

She read on in the paper. The article was only a few columns long. A related note mentioned that after the trial, Captain George Stevens had been taken into custody and charged with accepting bribes in exchange for performing his official duty. Minnie smiled wanly. Good.

The door opened. Robert stood in the hall, a book clutched to his chest. He met her eyes, his expression wary.

“You’ll have to excuse me if I make a hash of this,” he said quietly. “But I’ve never done it before.”

“What are you doing?”

In answer, he walked into the room and laid the leather-bound volume on the chest of drawers near her.

It was the primer she’d bought him the other day. “I…” He looked down and then looked up at her. “I decided what these letters stood for,” he told her. “I thought I might tell you.”

It took her a moment to realize that he was nervous. He glanced at her sidelong and opened the book to the first page.

“A,” he said, “is for all the ways I love you.”

That fierce prickle of tears stung her eyes with renewed force. She blinked, unwilling to let them cloud her vision. She wanted to see him, to make out the details of his pale, tousled hair, the way he bit his lip.

He looked away. “This is stupid,” he muttered, reaching for the corner of the cover. He’d almost slammed it shut before Minnie realized what he was doing and insinuated her hand between the open pages.

“No!” she protested. “It’s not.”

His hand hovered over hers. He swallowed.

“There is nothing stupid about your telling me you love me. Ever.”

“Oh,” he said quietly. He seemed to take a few moments to absorb that before he opened the primer again. “A is for ‘All the ways I love you.’ There are more than twenty-six, but as this is the alphabet we have, I’m going to have to restrict myself. At least for now.”

He turned the page to a brilliant scarlet B, illuminated the way one might see in a medieval manuscript. Beech trees made up one side of the letter, and a butterfly perched on the top of the curve of the B. “B is for ‘But I am going to make mistakes.’ Something I am sure does not come as a surprise to you.” He looked at her and turned the page. “C is for Confession. I don’t know how to do this. I don’t know how to be a husband. I don’t know how to be a father. All I learned from my father is how not to do it—and that is rarely any guide. But…” Another turn of the page. “D is for Determination.” Another page-flip. “E is for Eternity, because that’s how long it will take before I give up again. F—that’s for Forgiveness, because I think I’ll need a great deal of that, before I start to get things right.”

“You are getting things right at this very moment,” Minnie said with a smile. “Keep on.”

He nodded and turned the page. “G is for… G is for… G is for ‘Good heavens, I should have written these down.’ I’ve forgotten.”

Minnie found the corners of her mouth twitching.

He frowned in perplexity. “Really. I have no idea what comes next. I puzzled them all out in my head, and they were going to be utterly brilliant, and when I was finished, you were going to leap in my arms and everything would be better.”

Minnie leaned over and flipped a few pages over until she found the letter M. This was the page that had been on display in the bookshop when she purchased it. M was done in blues and blacks with hints of gold, the silhouettes of mulberry bushes making the dark shape of the letter against a moonlit sky. This M, perhaps, evoked midnight.

“This is the most important one,” she said. “M is for Me. I’m yours, even when you make mistakes.” She tapped it.

He stepped forward and slowly, slowly pulled her into his arms. “Minnie,” he said, “my Minerva. What would I ever do without you?”

“There’s only one other letter that we need to talk about.” She turned back one page. “L is for love. Because I love you, Robert. I love you for the kindness of your heart. I love you for your honesty. I love you because you want to abolish the peerage. I love you, Robert.” She pulled him close. “I’m not going to toss you out for one mistake.”

“But I—”

She shook her head. “We’ll get into that later. For now, Robert… There are other things that demand our attention.”

“Yes,” he said slowly.

“There is a crowd of reporters downstairs,” she said, “and we’ve just told everyone who I really am.”

“I’ll get rid of them.” He stood.

She held up one hand. “No,” she said slowly. “I don’t think that will be necessary.”

“DO YOU EXPECT TO INTRODUCE THE DUCHESS in society?”

“What does the Dowager Duchess of Clermont think of all this?”

“Why did you write those handbills? Is it part of a parliamentary ploy?”

As Robert stepped into his front parlor a few hours later, the shouted questions overwhelmed him, rising atop one another, adding up to indistinguishable cacophony. The sun had set by now; the oil lamps burned brightly, and the bodies packed in the room had brought the temperature up above the level of comfort.

The newspapermen had been invited in fifteen minutes earlier, and apparently they’d made

themselves comfortable enough to scream inside his private residence.

He waited until Oliver had entered the room behind him before he raised his hand. The shouted questions continued, but as Robert gave no answer—and instead stared the men down—eventually the hubbub subsided.

“Gentlemen,” he said, when everyone had quieted down. “Let me explain what is going to happen. I have invited you into my home. I have offered you tea and sweet biscuits.”

More than one hand surreptitiously brushed crumbs off of coats at that comment.

“If you abide by the rules I set, all your questions will be answered and then some. But the man who raises his voice above a pleasant, conversational tone—that man will get tossed out on his ear. The man who speaks out of turn, he will be shown the door. If you behave like a mob, you will be treated as one. If, however, you act as civilized people, we will entertain all questions.”

“Your Grace,” a man shouted from the back, “why the rules? Is there something in particular you fear?”

Robert shook his head gravely. “Oliver.” He gestured behind him. “Please show the shouting gentleman to the door.”

“Wait! I didn’t—”

Robert ignored the man’s protests, letting the others watch him be escorted out of the room. When the door closed on his babbled explanation, he turned to the remaining crowd. There were maybe twenty of them, perched on chairs raided from the other rooms. They all had their notebooks out. Forty eyes watched him warily.

“There are no second chances, you see,” Robert said. He heard the door open once again behind him. “Oliver, if you would please demonstrate the proper way to ask a question?”

His brother went to stand next to the nearest newspaperman and then raised his hand quietly.

Robert gestured at him. “I acknowledge the gentleman on the side.”

“Your Grace,” Oliver asked in a normal speaking voice, “why have you set these rules? Are you afraid of something?”

“An excellent question,” Robert said. “I have established these rules because, in a few moments, my duchess will be joining me, and I have no intention of exposing her to a howling mob.”

The men sat up straighter at that, leaning forward.

“You see,” Robert said, “it is the manner of asking that I care about. All questions will be entertained—although those that are too personal, we may decline to answer. Would anyone like to start?”

Glances were exchanged among men, as if they were all afraid to get it wrong. After a few moments, a man in the back diffidently raised his hand. Robert nodded to him.

“Your Grace,” the man asked, “why did you marry Minerva Lane?”

“I wanted a duchess who was beautiful, clever, and brave more than I wanted one who was well-born. I didn’t need money. The fact that I was also in love with her was a welcome bonus.” Robert indicated another man. “You’re next.”

“Does she wear the trousers in your marriage?”

It was a question Robert suspected he’d hear again and again, over and over, until he answered it to everyone’s satisfaction.

“Do you want to know the first thing she did with my money?” Robert asked. “She visited a modiste in Paris.”

That brought a chuckle.

“Trust me,” Robert said, “anyone who looks as lovely as my wife does in skirts and a corset has no intention of wearing trousers.”

Heads bent, scribbling down those words.

Minnie had been right. They have a pattern in their mind for what a woman should be, she’d said. On the one hand, it’s a pack of lies. But you can use those lies against them. Show them that I match the pattern in one respect, and they’ll not question whether I am different in another. She had smiled. In my case, it’s quite simple. I like pretty clothing. If we can make them see that, they’ll not ask about anything else.

“This is all well and good,” another man said when Robert called on him, “but do you believe that the young Minerva Lane induced her father to defraud others, that she was the cause of his conviction and untimely death? And if so, has she repented of it?”

Robert gritted his teeth, felt his temper rise, but he forced himself to calmness. “No,” he said. “Her father opened the false accounts. Her father told lies to his compatriots when she was not present. Common sense suggests that when he was caught and faced the gallows, he was willing to tell another lie to save himself, no matter who it harmed.

“The Duchess of Clermont has suffered enough for her father’s falsehoods,” he said. “In this, I must claim the right of husband.” He smiled tightly. “And so I’ll beat the stuffing out of anyone who suggests otherwise.”

His pronouncement was met by the sound of a dozen pens scratching against paper.

If you say that, Minnie had said, you know you’ll have to do it. At least once.

He was looking forward to it.

“Speaking of whom,” Robert said, “I do believe it’s time for me to fetch her.”

He turned around, aware of the soft susurrus that arose behind him. He opened the side door and stepped through.

Minnie was waiting in the adjacent room, hands clasped, pacing from side to side.

He stopped at the sight of her. She was wearing a gown he’d never seen before—one that had, no doubt, been commissioned in Paris between bouts of lovemaking. It was a brilliant crimson in color, the kind of gown that would draw every eye. She was laced tightly, emphasizing her curves. And she was wearing the rubies he’d given her.

She had a black lace shawl looped over her arms, which were otherwise bare, and flowers in her hair. But to all this, she’d added something he’d only seen in paintings from the last century. She’d added a simple black beauty patch at the corner of her mouth. It drew the eye to her scar, made that web of white across her cheek seem like a purposeful decoration instead of a reminder of a senseless act of violence. The very modernity of her gown, coupled with that antique fashion, made her seem like a creature from no century at all.

He realized that he’d stopped dead, staring.

“You know, Minnie,” he said, slightly hoarse, “you’re ravishing.”

“Am I? Your mother hates the patch,” she said. “Are there many of them?”

He went to her. “Almost twenty. But I’ve done my best to frighten them into civility. Are you sure you want to do this?”

She drew in breath; that diamond shuddered on her bosom. “Positive.”

He took her hand. “Because I’m willing to send them to the devil…”

Her palm was cold, clammy, her breath a little rapid.

“…and I’ll be here by your side the entire time,” he said. “Nobody will come close. I promise.”

“I know.” She squeezed his hand and then, together, they walked back to the front parlor. She paused in the entrance. He wasn’t even sure if it was nerves that stopped her or if she simply wanted to make an impression.

In any event, it was clear that she had. The men let out little gasps of disbelief—as if they expected, somehow, that she would have shown up at the door in coat and trousers. And then they scrambled to their feet.

Minnie smiled. Robert, holding her hand, could feel her pulse racing in her wrist, could feel her fingers digging into his palm as all those eyes fell on her. He knew how much that smile cost her. He also knew that if they’d shouted at that moment, if they’d made any noise at all like a mob, she might have passed out right then. Instead, the men were silent as death, not wanting to be tossed out.

He conveyed her to the divan at the head of the room, seated her, and then sat himself.

The divan was on a little bit of a raised platform.

Minnie looked around, taking them all in. “Well,” she said. “I suppose this is as close as I’ll come to a throne.”

That drew a surprised laugh from the crowd.

“You’ll have to excuse me, gentlemen.” Her voice was quiet, so quiet that everyone strained forward to hear her. “I’ve asked for sile

nce. My voice is not loud, and I am nervous.”

A hand went up at that. “Are you afraid of what truths we might uncover?”

A bold question to pose to her face. Minnie didn’t flinch.

“No,” she responded simply. “My fear is more primal in origin. When I was twelve…” She paused, took a measured breath, and continued. “Well, I believe you all know what happened when I was twelve, from my father’s statement in the courtroom to the mob that surrounded me afterward. They left me with this scar.” She touched her cheek. “Ever since then, large groups have made me faint of breath. I cannot bear to have so many eyes looking at me without remembering that time. In fact, I’m grateful for you all taking shorthand. It’s far better than having you stare at me en masse.” She said it with a deprecating smile, but her fingers were still tightly clenched around Robert’s.

Pens scribbled away at that. They wouldn’t detect what Robert could see so clearly—the pallor of her cheeks, the light pink of lips that were usually rose.

“Even now,” Minnie said, “all these years after, thinking about it makes my hands tremble.” She disentangled her hand from Robert’s and held it up in proof. “If there were ten more of you, I am not sure I could do this. And if you were shouting, I might actually pass out.” She gave them another smile. “That is what happened in the courtroom today.”

“How will you attend balls, parties—the sort of gatherings where duchesses are obligated to make appearances?”

“I am sure,” Minnie said, “that I will receive many kind invitations from my peers for precisely those events.”

They’d discussed that exact question, going over it again and again, until each word was perfect.

“I am also sure,” she said, “that everyone will understand that when I refuse those invitations, no malice is intended. Over the course of the next few years, however, my husband and I will be hosting a series of smaller events. I will be overseeing a number of my husband’s charitable concerns, and I feel confident that I will come to know many of my peers that way.”

“And you’re not afraid that you’ll be shunned for your prior history?”

Her Every Wish

Her Every Wish Midnight Scandals

Midnight Scandals After the Wedding

After the Wedding The Heiress Effect

The Heiress Effect Unraveled

Unraveled The Suffragette Scandal

The Suffragette Scandal The Year of the Crocodile

The Year of the Crocodile The Duchess War

The Duchess War What Happened at Midnight

What Happened at Midnight The Countess Conspiracy

The Countess Conspiracy Proof by Seduction

Proof by Seduction Unlocked

Unlocked Trial by Desire

Trial by Desire The Governess Affair

The Governess Affair Unveiled

Unveiled The Lady Always Wins

The Lady Always Wins Trade Me

Trade Me Unclaimed

Unclaimed This Wicked Gift

This Wicked Gift The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister)

The Duchess War (The Brothers Sinister) Hamilton's Battalion: A Trio of Romances

Hamilton's Battalion: A Trio of Romances The Turner Series

The Turner Series The Suffragette Scandal (The Brothers Sinister)

The Suffragette Scandal (The Brothers Sinister) Seductive Starts

Seductive Starts The Pursuit Of…

The Pursuit Of… Hamilton's Battalion

Hamilton's Battalion The Carhart Series

The Carhart Series Seven Wicked Nights

Seven Wicked Nights This Wicked Gift (A Carhart Series Novella)

This Wicked Gift (A Carhart Series Novella)